I’ve been thinking a lot about mistakes lately.

One of my most popular classes is titled “Oops!” The class hits home with knitters and crocheters: sometime, somewhere, we all are going to make a mistake. Probably even more than one mistake. And if it’s a big enough mistake, it’s going to need to be fixed. It’s a simple premise for the class. Let’s take the pressure off making mistakes, and deliberately make them – and then learn how to fix the mistakes we’ve created. Oops is a class, that, at it’s heart, is about being human. Instead of pretending that mistakes don’t happen, it faces them head-on.

I’ve heard it quoted a couple of times that in Navajo rug work the weaver puts a deliberate “mistake” into their work: the idea being that only the Creator is perfect. You hear this idea echoed in Indian or Persian rugs, or in Islamic geometric designs. While some people believe the myth is not true, there’s a point to be made in the story: by being human, we make mistakes, and in some ways we should make peace with it.

The Yarn Harlot’s written about mistakes dozens of times. Elizabeth Zimmerman held the idea that there are no mistakes in knitting, as long as the results turn out the way you want. Heck, mistakes are so common in patterns that there’s a word for it: errata.

Yet, two weeks ago I was a stew of anxiety as I went through tech editing for three of my patterns coming out in the fall.

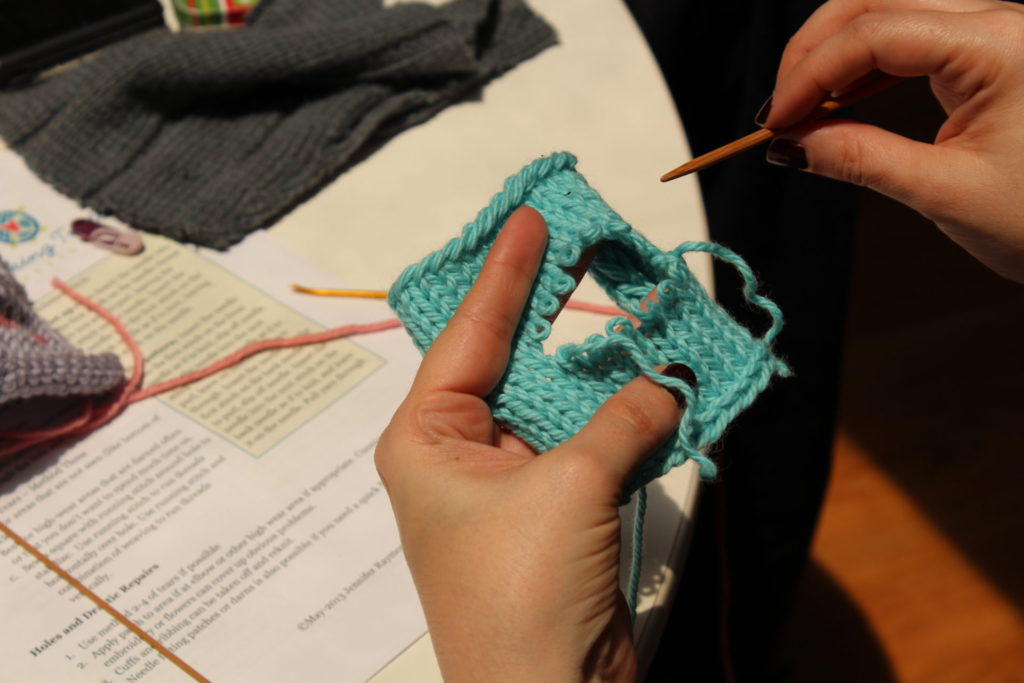

Fixing a hole formed in a worn-out glove

It’s funny: a large part of my income comes from doing away from imperfections: repairing broken things, and fixing mistakes in pieces seen as unsaveable.

Yet, when it comes to my *own* mistakes, I’m hesitant to talk about them.

Perhaps it’s because of the scale. To me, a mistake in a blanket affects nothing except the blanket. If I make a mistake cooking, or gardening, or in any of my personal activities, the only person harmed is myself (and perhaps Mr. Turtle, if he’s forced to eat my cooking). In contrast, a mistake in a pattern affects someone else’s life. It can inconvenience them. A mistake in a pattern can take hours for a tech editor to untangle; in worst cases, it can derail publishing deadlines and hurt the bottom line. Mistakes on that scale can be costly.

I’m not one to let go of my own mistakes lightly. In 10th grade, on a field assignment, I broke a thermometer that my teacher was letting me borrow. I was heartbroken and that night I cried myself sick, thinking about telling my teacher the next day that I’d let him down. The whole day before I could go see him, I worried the situation over like a sore tooth: poking and prodding at it, envisioning the worst case scenario. By the time I got to last period when I could speak to him, I was physically sick and trembling. My small mistake had become so big in my mind it has physiological effects. When I went to tell him what was wrong, I ended up just crying from the stress.

It’s why I love working for myself: I can choose the people, and the situations, where I’m held accountable.

I’ve grown up since 10th grade, but big mistakes still have the ability to immobilize me, at least a little. Crafting an email in response to an irate customer can still leave me feeling queasy.

So two weeks ago, when I had not one, but two patterns in tech edits with some significant problems, I struggled to keep my composure. In a conversation to my friend Becca, she put things into perspective.

A while back I hired a woman to help me crochet some pieces that were on a deadline. They were samples, and the patterns were already written, but they needed to be worked up in different yarn. I had very specific instructions. I handed off the yarn to her, with a firm emphasis that if problems came up, if her gauge was off, if she made a mistake, she should contact me right away. I knew that she might make mistakes, but as long as she communicated with me, I could manage things.

Unfortunately, when she made mistakes, as sometimes we are wont to do, she kept working the pattern, hoping that if she went further the mistake would be less obvious. Instead, when I got the pieces, I had to do quite a bit of work to fix things she hadn’t shared with me.

I was angry. It wouldn’t have been a problem if she had just gotten in touch with me, but instead, she waited until the deadline to inform me of the problems. It left me with very little time to do damage control.

In the same manner, Becca pointed out, I should handle the mistakes I make. If I made a mistake, I should be upfront about it. I shouldn’t cover it up. Instead, I should communicate what my problem is, and ask for help.

Not so very easy.

Why am I talking about all this?

Well, I’m thinking about how mistakes are viewed in crafting, in the knitting and crochet industry, and in my own personal life. And I’m thinking about ways I can both respond to mistakes I make, and other’s make, with more grace.

Have you made a mistake in your personal or professional life? How do you handle them? I really, really would like to know.